Chapters

Uprising of Spartacus in 73-71 BCE was the greatest spurt of slaves in the history of ancient Rome. The result of the rebellion was the decision to gradually improve the existence of slaves.

Background of events

With the territorial expansion of Rome, more and more slavery latifundia began to emerge. The ruthless exploitation of employees led many to several uprisings. The fate of slaves in province and schools for gladiators was particularly difficult. Warriors who had planned an outbreak of an armed uprising against Roman exploitation and social injustice waited for a charismatic commander.

Spartacus

Spartacus was a man of strong character and intelligence. He probably came from Thrace1, a country that was still independent (then Thrace would become one of the provinces of Rome), but already exposed to Rome’s retaliatory actions. Thrace located on the Balkan Peninsula was known for a well-trained infantry using sickle swords.

Spartacus initially served in the Roman army as a Thracian mercenary. He became a good soldier. However, later, as a result of his bad behaviour and lack of discipline he was sent to the gladiator school in Capua (the west coast of the Apennine Peninsula). Spartacus, as an excellent gladiator, for some time served as a fencing teacher there, he taught valuable “pieces” of this fight. There, for killing another gladiator, he was transferred to Lentulus Batiatus’ school, a very difficult and high-security one. The name “Spartakiad”, so mass form of sporting events, comes from his name. He was a skilled fighter.

Plutarch mentions that Spartacus had a wife, from the same tribe. After his enslavement, she was also sold as a slave girl. We also know the prophecy that Plutarch gave us:

It is said that when he was first brought to Rome to be sold, a serpent was seen coiled about his face as he slept, and his wife, who was of the same tribe as Spartacus, a prophetess, and subject to visitations of the Dionysiac frenzy, declared it the sign of a great and formidable power which would attend him to a fortunate issuee.

– Plutarch, Crassus, 8

Uprising

In 73 BCE, a revolt led by Spartacus broke out. Its causes are found in the ill-treatment of gladiators. Around 70 gladiators, mostly Thracians and Gauls, accompanied Spartacus in this successful operation; the rest, between 120 and 170 slaves, died or remained in captivity. Armed with kitchen knives (gladiators could not have their weapons behind the arena), they repulsed the guards’ attack and got free. Already outside the city walls, they fought a victorious battle with the pursuing squad, thus gaining weapons. It is worth mentioning that the gladiators did not want to fight with gladiatorial weapons, treating them as disgraceful. Moreover, this type of weapon (e.g. crested helmets or heavy greaves) was impractical on the battlefield and people tried to arm themselves in the way that the Roman army fought.

Battle of Vesuvius

After initially plundering the fertile farms of Campania, Spartacus led his gradually expanding force of fugitive slaves to Mount Vesuvius, where he camped in its crater and waited for the Romans to besiege it. The slaves gathered on Mount Vesuvius chose – Crixus and Oinomaos – to be the chiefs. The initial, small group of insurgents grew quickly, powered by escapes from neighbouring estates. Vesuvius turned into a fortress that sheltered 10 000 people. They became the terror of all the rich Romans nearby. The Senate finally decided to send a regular army against the rebels. The Roman commander was Claudius Glaber, sent by praetor Publius Varinius, whom the Senate commissioned this operation.

When the Romans were close to the encampment with around 3,000 soldiers, Spartacus told his companions to make rope ladders from the climbers, thanks to which they quickly got to the bottom of the volcano. This action in the night allowed to surround Roman troops, shock them and surprise them with a victorious attack from the back.

Growth of uprising

In subsequent skirmishes, Spartacus defeated the praetor Varinius himself, who informed the senate about the problems in suppressing the rebellion and sent requests for more funds to fight the slaves. The Senate, which previously did not believe in the seriousness of the problem, finally decided to intervene. Against the rebels, it was decided to send 4 legions, which were divided between the consuls Lucius Gellius and Lentulus Clodianus. However, before the fight began, the focus was on securing central Italy, recruitment and training of conscripts.

During this time, Spartacus gained immense popularity among the slaves who joined his army en masse. Some of them constituted the regular army, some were responsible for providing provisions, and others for craft work. In the huge mass of people, there were also women and children, which meant that Spartacus had to lead not only a regular and punitive army, determined to fight but also ordinary civilians.

Spartacus decided to leave the plundered Campania and go south through Lucania to what is now Calabria. Gladiators, not disturbed by the Roman army, could rob and ravage other lands without any obstacles. According to ancient sources, the slave army was extremely cruel. Due to the lack of engineering skills, large cities were skipped and focused on easy targets that brought food and wealth. The chief tried to curb the ruthlessness and cruelty of his comrades, but it was hard to do. The population left all areas that were in the way of the insurgents and took refuge in the mountains or other safe places.

Spartacus’ army finally reached Cosentia (now Cosenza). After deliberation, it was agreed that Italy was not a place for rebels and that no Italian city or tribe would be able to cooperate with the slaves. Therefore, it was decided that the best solution was to leave the Apennine Peninsula, cross the Alps and spread to Gaul, Germania or Thrace. For this, however, Spartacus’ army had to cross the entire peninsula and defeat all Roman armies. The army set out at the turn of April and May 72 BCE. heading through Apulia (eastern Italy) and scavenging for food along the way.

It is worth mentioning that new volunteers joined Spartacus all the time. They were haggard and ragged vagabonds, prisoners and runaway slaves who were freed by gladiators from their great estates. At that time, the army of gladiators reached 60,000 people.

Battles with conular armies

The next year the Senate sent 4 legions against the rebels. The commanders of the Roman army were: consul Lucius Gellius and Lentulus Clodianus.

When in 72 BCE the insurgent army of Spartacus’ slaves marched north through Italy, towards the Alps, the insurgent forces split up. Gauls and Germans, under the command of a certain Crixus, went ahead to plunder Apulia (eastern, central Italy) freely. However, Crixus’ army was defeated by the Roman army and he himself was killed; 20,000 insurgents were to die. It was the first major victory of the Romans in the fight against the slaves of Spartacus.

At the same time, the main army of Spartacus was engaged by other Roman troops, under the command of consul Lentulus, not to come to the aid of Crixus’ army. Spartacus finally defeated both the legions of Lentulus and later, the victorious troops of consul Gellius and praetor Arrius.

When the battles near Mount Garganus were over, Spartacus ordered his men to bury their fallen comrades with dignity. Moreover, as revenge for the destruction of his army and the killing of Crixus, he organized “gladiator fights” in his camp. This time, however, Roman prisoners fought to the death, who was to honour the fallen with their blood, including Crixus. It is worth mentioning that fights at funerals were the prototype of gladiator fights in Rome. High-ranking Romans organized slave fights to honour a deceased family member (called munera). Over time, however, Roman politicians noticed the electoral benefits of organizing games and gladiator fights became entertainment. By organizing a gladiator fight with Roman prisoners, Spartacus mocked the torturers he fought with.

At that time, Spartacus, according to Appian, already had 120,000 infantry under his command. Due to the desire to maintain a fast march, he decided not to accept new fugitives, butchered pack animals and left military equipment useless. According to the Romans, it could have been a signal that Spartacus was preparing to approach the capital.

The slave army headed north again and in the area of Picenum once again defeated the army of consuls combined with local troops; including settled veterans. Then, at Mutina in Cisalpine Gaul, another Roman force of praetor Gnaeus Manlius and proconsul Gaius Cassius was destroyed.

During this time, there was an incomprehensible change of plans for Spartacus and other commanders. With the Alps at their fingertips and the possibility of leaving Italy, the insurgents turned back and again headed south of the peninsula. To this day, researchers argue about the motives that led the insurgents to change the direction of the march. It is believed that what was feared above all was the approaching winter in the Alps; the people living along the way, which may not be favourable to the immigrant masses of slaves; or simply internal division in Spartacus’ army. Whatever the reasons, the vast massifs of slaves turned back and threatened Rome itself again.

Taking command of Romans by Crassus

The inhabitants of Rome experienced a period of great fear, comparable to the panic that prevailed during the war with Hannibal. It was feared that slave troops would attack Rome. In this situation, the Senate granted extraordinary powers of attorney to the praetor Marcus Licinius Crassus, discrediting the Roman commanders and giving him special powers in Italy. Giving full and independent command of a great force to Crassus was a truly unique move on the part of the Senate. The senators still remembered the generals Marius or Sulla, who thanks to the army concentrated in their hands enormous power, which was beyond the control of the patricians. In the case of Crassus, the same was feared; however, fear for the fate of the state prevailed. Crassus mobilized great forces against the rebels. For this politician and millionaire, capturing Spartacus became a priority. This achievement would allow him to easily defeat his political enemies and raise his own position on the stage of Rome. This is how Florus described the moment:

Elated by these victories he [Spartacus] entertained the project – in itself a sufficient disgrace to us – of attacking the city of Rome. At last a combined effort was made, supported by all the resources of the empire, against this gladiator […]

– Florus, Epitome, 2.8.11-12

Crassus, probably together with the then still young and inexperienced Julius Caesar was able to inflict certain defeats on Spartacus’ troops. However, Spartacus was not focused on seeking a clash with the enemy, who had gathered a powerful army of about 10 legions. His goal was to reach the tip of Italy and try to transport the slaves to Sicily, where he saw a chance to continue fighting for freedom and independence. Unexpectedly, however, these plans were thwarted by the betrayal of the pirates, who accepted the payment but sailed away.

Unexpectedly for Spartacus, at that time Crassus’ army was vigilantly following his troops and began erecting a series of fortifications (ditches and walls) in order to cut off his way back. These works were really impressive, as they stretched for about 55 km and made it possible to completely enclose the approximately 100,000 insurgent armies in a small space, without the prospect of escape and gathering supplies.

Subsequent attacks by the insurgents on the Roman fortifications brought heavy losses to the insurgents. Ultimately, however, during unfavourable weather and cover of night, the long line of defence did not cope with the attack of the insurgents and 1/3 of them managed to break through. Frontinus reports that Spartacus used human shields in the form of cattle and prisoners to approach the fortifications, and used human and animal bodies to fill the ditch and create an embankment.

Soon a decisive split took place in the army of rebels remaining with Spartacus. Two Gallic chieftains left the army, taking their supporters with them, which definitely weakened Spartacus. These troops fell into Crassus’ planned ambush, and Spartacus was unable to come to their aid.

In the meantime, support appeared in Italy in the form of the victorious general Gnaeus Pompey, who came from Spain, and the army of the governor of Macedonia – Lucullus – landed in Brundisium. Spartacus knew he had to take a risk and defeat Crassus before more Roman armies joined together.

Fall of Spartacus uprising

Crassus, like Spartacus, was looking for a decisive clash at all costs. The politicians who came, and especially Pompey, could take away from him the glory of victory. Moreover, the period of six months in which he had pledged to defeat the rebels were coming to an end.

The next battle took place in 71 BCE. on the Silarus river (now Sele), in the southwest of the Apennine Peninsula. Plutarch relates that when Spartacus rallied his army for battle, he was given a horse. However, he drew his sword and killed the animal, claiming that if he defeated the Romans, he would have enough beautiful horses, and when he lost, he would not need them anymore. This is how the Greek historian Appian of Alexandria describes the battle:

At the news that he had haarived in Brundisium, and Lucullus returning from the war against Mithridates, Spartacus, completely desperate, struck at Crassus with still great forces at that time. There was a long and fierce battle, predictable, tens of thousands of desperate people; in the course of the battle Spartacus was wounded with a spear in his thigh, but he only kneeled down and, shielding himself, fight the attackers, until he was encircled with the great number of people who gathered around him. The rest of his army was in a massive disarray staggering in mass, so that in the slaughter the countless people were killed, while the Romans lost up to a thousand soldiers; Spartacus’s body could not be found. A large number of survivors who escaped from the battle hid in the mountains, so Crassus followed them. Divided into four groups, they resisted until they were all dead except for 6 000 people who were captured and hanged along the entire road from Capua to Rome.

– Appian of Alexandria, Roman History, XIII.120

The death of Spartacus is described by Plutarch of Chaeronea:

Then he made straight for Crassus himself, charging forward through the press of weapons and wounded men, and, though he did not reach Crassus, he cut down two centurions who fell on him together.

– Plutarch, Crassus, 11

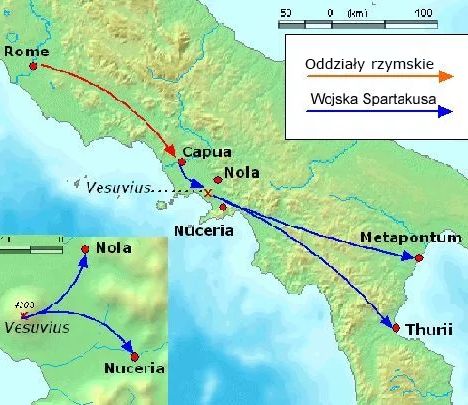

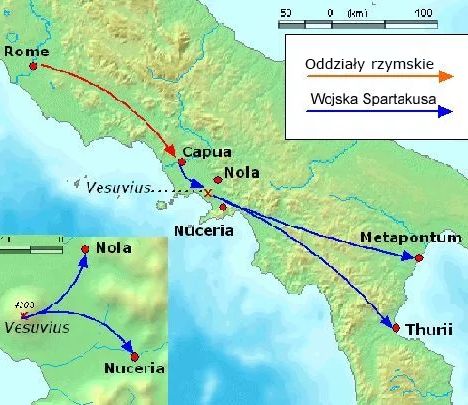

Course of Spartacus’ uprising |

|

I STAGE: The first tactical decisions of Roman troops and Spartacist supporters in winter 72/73 BCE |

|

II STAGE: Events of 72 BCE (according to Appian). |

|

III STAGE: Events of 72 BCE (according to Plutarch). |

|

IV STAGE: Events of early year 71 BCE Crassus takes command of the Roman legions, confronts the rebels and forces Spartacus to retreat to Lucania near Messina. |

|

V STAGE: In the last period of wars in 71 BCE Spartacus forces manage to pull the Crassus legions from the “ring” and head north towards the Petelia Mountains. Ultimately, however, the situation forces Spartacus to turn back and fight a battle that decided about the fall of the rebellion. |

Consequences

The slave rebellion was finally suppressed by Crassus. Pompey’s army did not take a direct part in the fighting, but by marching from the north they captured around 5000 Spartacan rebels after their defeat at Silarus river. After this action, Pompey sent a message to the Senate, in which he confirmed the victory of Crassus in an open battle, and at the same time considered his actions as decisive at the end of the conflict. In this way, he brought upon himself the majority of glory and at the same time the hostility of Crassus.

Both Pompey and Crassus regarded themselves as the victors of the war and when they returned to Rome with their legions, they refused to dissolve the units and decided to set up camps outside the city. In the year 70 BCE, both political leaders received consul positions. Interestingly, such a situation was illegal according to Roman law, especially with regard to Pompey, who was too young and did not hold the required offices (praetor and quaestor). Certainly, the tender card was the presence of legions under the city walls, which the senators feared.

As for the insurgents – most of them died in direct combat. Six thousand prisoners captured by Crassus’ legions were crucified on the Appian Way from Rome to Capua, where the rebellion began. It was supposed to be a lesson and a warning against a possible outbreak of another uprising2.

According to Roman sources, some of the insurgents took refuge in inaccessible places and either joined the existing bands of robbers or founded their own.

The uprising brought about the destruction of large areas of Italy, the slave owners suffered heavy losses, and the poor also participated in the uprising.

Improving life of slaves

Dangerous Roman authorities imposed strict discipline on future generations of gladiators, while at the same time reducing the role of slavery in the economy. Fearful of successive speeches, wealthy latifundia owners resigned from slave labour and replaced them with free people in the countryside. This situation was promoted by the fact that the Roman Empire gradually gave up conquests and decided to stabilize the borders. Such activities could be seen over the years from the reign of Augustus to the emperor Trajan, whose conquests have enlarged the territory of the country to the largest extent in history. Along with a small number of conquests, the number of slaves brought in, who were replaced at work by poor free people, decreased.

Fear of a possible next outbreak of slave rebellion led to the gradual improvement of the legal existence of slaves. Emperor Claudius in the middle of the 1st century CE forced the law according to which the murder of an old or infirm slave was considered murder, and the slaves abandoned by their masters were to become free people.

Emperor Antoninus Pius in the middle of the 2nd century CE broadened slavery rights, including holding the owners responsible for killing a slave, forcing them to sell a slave who was ill-treated and providing a slave with the right to appeal to a neutral third party.

Certainly, these changes were introduced too late, but to a large extent, the War of Spartacus contributed to the improvement of slaves’ lives. As it turned out, it was the last slave uprising in the Roman Empire.

Important battles of war of Spartacus

- 73 BCE – battle of Mount Vesuvius

- the first won battle for the insurgents. As a result, 70 gladiators defeated the forces of 3 000 legionaries

- 72 BCE – battle of Mons Garganus

- the victory of the Romans led by Lucius Gellius over the forces of 30 000 insurgents led by Crixus (he died)

- 72 BCE – battle of Mount Camalatrum

- Romans’ victory led by Crassus over the insurgents

- 72 BCE – Battle of Mons Cantenna

- Roman forces led by Crassus beat up insurgents led by Castus and Cannicus (both leaders died in battle)

- 71 BCE – battle of Petelia

- 71 BCE – battle of the Silarius River

- the last armed clash during the rise of Spartacus. As a result of the battle, Roman forces led by Crassus won the Spartacan insurgents. Roman losses were around 1000 killed, and losses of insurgents are estimated at 66 000 dead and prisoners. The death of Spartacus in battle put an end to the uprising of slaves and gladiators.