Chapters

Roman law had a significant impact on the development of European legislation. In addition to engineering, this was the second field in which the Romans were extremely successful.

However, the codification of Roman law itself took place relatively late. It wasn’t until the turn of the second and third century CE that Roman tourists began writing comments, which in codified form became one of the most valuable cultural heritage of medieval Europe.

The history of Roman law was adopted into three periods:

- period of archaic law – it lasts from the beginning of Rome, i.e. around 753 BCE to around the middle of the 3rd century BCE. The main source of law was customary law, which in sources is called mos maiorum or consuetudo. This period is based on the foundations of Roman legal thought, i.e. law of the XII tables;

- period of development and classical law – it lasts from the middle of the 3rd century BCE to 235 CE, which is equivalent to the death of Alexander Severus. It is divided into two subperiods: pre-classical law (until about 27 BCE) and classical law (from 27 BCE to 235 CE). The term Roman law is often used to refer to the law of that period;

- declining period (classic) – it lasts from 235 to 565 CE It is also divided into two subperiods: the classic period (from 235 to 527 CE) and the Justinian period (from 527 to 565) CE).

The oldest Roman law was customary, unwritten, i.e. it was passed down from generation to generation by oral means, which, as you can guess, led to abuse also by judges, especially since they came from the richest social strata and perpetuated legal inequality in the face of most plebeians. It was this factor that determined the creation of a special ten-person commission that edited the new code. The effect of the committee’s work was a set of laws written on twelve tables (law of the XII Tables), published between 451, and 449 BCE Most of the laws listed are dedicated to the protection of private rights. For many years it became the main source of law in ancient Rome and was never formally abolished. It enjoyed great respect in society, mainly due to the history of its creation, i.e. the adoption at the plebeian’s request. The text of the laws was written on wooden boards and put up in the Roman forum, which burned down during the Gall invasion in 390 BCE.

Custom (mos or mos maiorum) was of great importance in the later shaping of written legislation. Many elements of customary law were adopted, such as the prohibition of donations between spouses or the prohibition of marriages between relatives, which led to the fact that many customs survived in the form of an unwritten Roman state in the west.

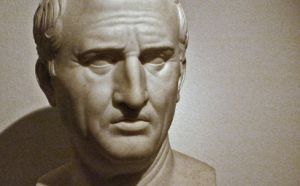

In Rome, the most concerned were citizens dealing with the law. Initially, the law was commented on by priests, and later, experts in law joined them. In addition to legal experts, there were also lawyers (oratores). They were practitioners, experts in legal formulas and court speakers. Interestingly, legal experts (today they would be legal advisors) or lawyers did not receive payment for their advice. This was prohibited by law. Other forms of payment, such as donations or inheritance, were allowed.

Some of the law experts earned huge fortunes and assets, such as Cicero, which set off on a long journey, which evening he stayed in one of his villas.

The trial judges were initially consuls, then prime ministers, and finally sworn judges elected from among the citizens.

The law in Rome was divided into two parts:

- Internal law concerned only Roman residents and citizens. This law changed for many centuries, having a completely different form in different periods of power. For example, during the republic, power was subordinated to senators and the People’s Assembly (including residents). Everyone could take part in discussions, and decide the fate of the state and the people. In those days freedom of speech was allowed in a sense. It was possible to comment on a topic, but without a larger picture under the title of the aristocracy. In turn, during the empires, the law changed drastically. Freedom of speech ceased to exist, although in a sense the senate and the people’s representative still existed. The wrong word to the emperor was severely punished and all opposition was levelled. However, the period of the empire was definitely better organized legally than before the time of the republic. The number of crimes and corruption dropped sharply, and the mighty “sat quietly under the broom” just to avoid being punished. Returning now to Rome’s internal structure in general, it should be noted that the law was respected and respected. What can’t be said about the second type of Roman law?

- International law was completely different. It should begin with the fact that the Romans considered world rule as their historical mission, which led to constant partitioning wars with neighbouring countries. Initially, they did not respect the cultures and traditions of the conquered lands. They carried out mass romanization consisting in forcing the conquered population to accept the Roman religion and its culture. Over time, however, Romanization slowed down, and the great area and multi-ethnicity of the state forced the Romans to relax the law. The Romans very willingly began to adopt the cultural patterns of other peoples and stopped forcing them to take over their religion. People did it voluntarily because it was profitable to be Roman. It happened that before the battle began, the Romans made sacrifices not only to their gods but also to the opponent’s gods so that they would go to their side. In short, they were very susceptible to the cultures of other peoples, and therefore, if they could benefit, they did not hesitate in accepting another god. The Romans knew the concept of a just war, but this did not mean a war of defence or in accordance with specific moral and political criteria, but only a war declared according to the assigned sacral-legal procedure. Rome acted in the name of development and spread to the world of science and civilization, which Rome was the only one to possess. For many, the war in Rome was considered the most legal way to acquire territory, property, and slaves.

Nevertheless, the Romans concluded international agreements with other countries. Two forms of such agreements were distinguished: friendship treaties (amicitia) and covenant treaties (societas). Another type of covenant was that Rome, as a stronger one, provided protection to the weaker state against external enemies in exchange for the provision of armed reinforcements and specific benefits in kind. The name of such an alliance is an international protectorate.

In Rome, great importance was attached to respecting the principle of immunity of deputies, calling them “saints”. They had much more freedom of action than ordinary citizens.

In Rome, the notion of the right of nations (ius civile) also developed, consisting of the fact that it was the right of citizens and no rights were granted to foreigners. This caused numerous disputes between foreign guests and Roman law. A special judge was appointed to settle these disputes (praetor peregrinus). In solving problems, he used the path of equity and reason, not Roman law. So a new law was created, ius gentium, which was very beneficial for foreigners and led to faster citizenship.

Marriage law

Marriage in ancient Rome was a loose relationship. For divorce (divortium) a statement (repudium) of one of the parties was sufficient; husband or wife. When the spouses cheated on each other, there were no grounds for complaint. He was punishable for infidelity.

Emperor Octavian Augustus established:

- death penalty for adultery with a married woman (adulaterium)

- for ordinary prostitution (stuprum) well-off citizens (honestiores) were punished by confiscating half of their property; those who had nothing (humiliores) received flogging. And they were driven out of the city.

However, the bachelors were offending, provided that the woman caught in prostitution did not come from the ruling house.

In addition to marriage, there was a cohabitation. On the inscriptions, women were often called concubinae; this also applies to Caesar’s partners. We often hear about plural concubines. The cohabitation in Rome was not much different from the cohabitation known now, it was the actual relationship of a man and a woman, who was treated as a lower form of marriage. He was very popular in Rome because of the prohibition of marriages between provincial officials and women from this province, and the prohibition of marriages by soldiers. In such cases, lasting relationships could only be regarded as cohabitation, which meant that those remaining in them were not punished for adulterium (according to lex Iulia de adulteris). Adulterium was a crime envisaged in August’s marriage laws and was understood as a relationship with a married woman and equated with stuprum, that is, a relationship with a widow or maiden. Initially, cohabitation was not a monogamous relationship, you could remain in it despite marriage with another person. Unions of people at least one of whom was a slave were called contubernium.

Court case

Everyone in the empire had to follow Roman law, and it was usually very strict. People who committed crimes, for example, were punished to discourage others from breaking the law. The poor were punished most severely, often in public. The rich could usually count on a milder punishment. All those charged with the crime were tried in the city’s basilica. The head judge and a group of citizens called the bench appeared at each trial. Together they decided on the guilt or innocence of the accused. In important trials, up to 75 citizens were asked to sit on the bench.

If he could afford it, he hired a lawyer. Lawyers often gave dramatic and emotional speeches in defence of their clients. Sometimes the accused had their hair washed and put on torn clothes to make the jury feel sorry. If someone was found guilty, the judge decided the sentence. Rich Romans who did not pay debts or taxes were often punished with huge fines. If they could not pay them, they would lose their property or citizenship. Other rich criminals were sent to distant parts of the empire and were forbidden to return home. Many poor people were sold into captivity, forced to work in underground mines or sent to the arena for gladiatorial fights. There were cruellest punishments – many criminals were beheaded, thrown to wild animals or crucified.