Chapters

| Name | Lucius Septimius Severus |

|---|---|

| Ruled as | |

| Reign | 14 April 193 – 4 February 211 CE |

| Born | 11 April 145/6 CE |

| Died | 4 February 211 CE |

Septimius Severus was born on 11 April 145 or 146 CE in Leptis Magna (present Libya) as Lucius Septimius Severus (Lucius Septimius Severus). It ruled from the year 193 to 211 CE. He won the civil war that broke out after the death of Commodus and stabilized the situation in the state. He started a new Severan dynasty.

Family

He came from a wealthy and respectable family with Punic ancestry pedigree. His father was Publius Septimius Geta, and his mother Fulvia Pia. On the mother’s side he had Italian ancestry, and on the father’s side, Punic.

Severus’ father did not have any important political status; however, his two cousins, Publius Septimius Aper and Gaius Septimius Severus, held the consul’s office during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius. His mother’s ancestors belonged to gens Fulvia and were a respected patrician family from Tusculum. For unknown reasons, they moved from Italy to North Africa, where they eventually settled.

Septimius had siblings: the older brother, Publius Septimius Geta and his younger sister, Septimia Octavilla. His maternal cousin was Gaius Fulwius Plautianus, prefect of pretorians and consul.

Political career

C. 162 CE Septimius Severus went to Rome to start his political career. Being recommended by his “uncle” Gaius Septimius Severus, he received the right to enter the senatorial state from the emperor Marcus Aurelius. Becoming a member of the senatorial circle was a precondition to start cursus honorum and, in the future, to take part in the Senate’s proceedings. Regardless of this fact, historians believe that the 60s of the 2nd century CE were full of difficulties for Severus and his political career.

Septimius probably served as a lower official (vigintivir), controlling the condition of roads nearby or in the city and as a lawyer in court. Interestingly, Septimius bypassed the position of the military tribune and was thus forced to delay being a quaestor (possible after reaching the age of 25). At that time, in 166 CE in Rome broke out a plague of measles or smallpox (so-called Antonine Plague).

During the inhibition of his career, Severus decided to return to his home in Leptis, where the climate was healthier and the disease could not spread to such an extent. According to the Augustan History (perceived as an uncertain source), he was hunted for adultery at that time, but the case was finally dismissed. At the end of 169 CE, Severus reached an age that enabled him to be a quaestor. On December 5, he took the office and was officially admitted to the Senate.

Between 170 and 180 CE, Septimius’ actions are mostly unknown. We know, however, that he filled a large number of offices at that time. The Antonine Plague clearly slaughtered the Roman population (including the senatorial state), and therefore the Empire needed as many talented men as possible to take offices. After finishing quaestorship in Rome, Severus was sent to Baetica (southern Spain) with the same mandate. However, chance occurrences prevented him from continuing his function.

At that time his father died, which forced Septimius to leave Then the Mauri tribesmen invaded southern Spain. Control of the province was handed over to the Emperor, while the Senate gained temporary control of Sardinia as compensation. Thus, Septimius Severus spent the remainder of his second term as quaestor on the island.

In 173 CE the kinsman of Septimius Severus – Gaius Septimius Severus was appointed proconsul of the Province of Africa. Elder Severus chose his cousin to be one of the two legati pro praetore. With the end of the office, Septimius went to Rome and became the tribune of the plebs, with the distinction of being the candidate (candidatus) of the emperor himself.

Marriages

At the age of 30, in 175 CE, Septimius married Paccia Marciana, a woman from Leptis Magna. The young “careerist” probably met her during his tenure as legate under his uncle. Her name suggests her wither Punic or Libyan roots – but nothing more is known. Septimius Severus does not mention her in his autobiography, it is safe to say that he highly respected her. During his reign, he built her many statues. The Augustan History claims that Marciana and Severus had two daughters, whose lives are not confirmed by other sources. Probably no child was born from their marriage.

Unexpectedly in 186 CE, Marciana died. 40-year-old Severus was still childless and looking for a new wife. He used to often check the horoscopes of his possible female candidates. The Augustan History mentions that Severus heard about a woman in Syria who was foreseen to marry the king. After hearing this information, Septimius found her and married her. It was Julia Domna. Her father, Julius Bassianus, came from a respected and rich family in Emessa. He served as a high priest to the local cult of the sun god Elagabal. Domna’s older sister, Julia Maesa, was the future grandmother of future emperors Elagabalus and Alexander Severus.

Bassianus accepted Severus’ proposal in early 187 CE and in the summer the couple married. The marriage turned out to be happy and successful. Severus always counted on the opinion of his wife, who was very well educated and interested in philosophy. Two sons were born from their marriage: Lucius Setimius Bassianus (later known as Caracalla – born on 4 April 188 CE) and Publius Septimius Geta (born on 7 March 189 CE).

Civil War

In 191 CE Severus received the command over the legions at Pannonia from Commodus. However, in 192 CE, the emperor was murdered, and Pertinax was proclaimed the new ruler, who then in early 193, was murdered by the Praetorian Guard. In response to this shameful transgression, Severus’s soldiers proclaimed him the new emperor in Carnuntum, from where he then hurried to Italy.

The successor of Pertinax in Rome was Didius Julianus, who outbid the prefect of the pretorians, Aemilius Letus, who also wanted to buy power from his subordinates, offering each soldier 25 000 sesterces. Eventually, however, after a short time, Julianus was sentenced to death by the Senate and killed. Severus took over the capital without any problems. He carried out the execution of Pertinax’ murderers and disbanded the rest of the Praetorian Guard, replacing them with his own men.

At that time, the legions in Syria proclaimed Gaius Pesensius Niger the emperor. There was also another rival to the throne, an earlier supporter of Didius Julianus, Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britain. Septimius decided to give him the rank of Caesar, which would satisfy his lust for power, and he went to the east to deal with Niger. In 194 CE he destroyed the usurper’s army in the battle of Issus and went to the Byzantium (Byzantion), where he ordered to cover the tomb of Hannibal with the best marble.. He ordered to raze the city to the ground, as the residents decided to support the usurper. However, after several years Severus decided to rebuild it and it is Septimius who is credited with starting the construction, on the ruins of the Greek city, a typical Roman metropolis. After a hundred years, his project was continued by Constantine the Great.

The following year, Severus devoted himself to suppressing Mesopotamia and other Parthian vassals who supported Niger. After defeating the enemy in the east, the emperor appointed his son Caracalla as the official successor to the throne, which meant a declaration of war to Albinus in Britain. He was proclaimed emperor by his soldiers and went to Gaul. Severus, after a short stop in Rome, went north to meet his opponent in an open field. On 19 February 197 CE Septimius Severus defeated the usurper Clodius Albinus in the battle of Lugdunum (today’s Lyon). His army ranged from 70 000 to 90, 000 soldiers (some sources mention c. 75 000 people) mostly composed of Pannonian, Moesian and Dacian legions. Finally, Albinus was killed, Severus ended the civil war and took full control over the empire.

Reign

Immediately after taking power, Severus had to face the rising power of the Parthians. In early 197 CE, Severus left Rome and went east by sea. He probably set out from Brundisium and arrived at the port of Aegeae in Cilicia, travelling to Syria by land. He gathered the army and crossed the Euphrates. He was accompanied by the King of Osroene, Abgar IX, who was forced to support the legions with his archers. His children were Roman hostages. The Romans were also supported by Khosrov I, the king of Armenia, who sent gifts, money and hostages. Severus and the army marched towards Nisibis (today’s Turkey), where Julius Laetus prevented the town from passing into the hands of the Romans.

In the following year (198 CE), the emperor led a much more effective campaign against the Parthian Empire, which supported Clodius Albinus during the civil war. The Romans managed to take over the capital, Ctesiphone, and the northern part of Mesopotamia. Herodian describes these events:

The army, sailing in a large number of ships, was not borne to its intended destination on Roman-held shores, but after the current had carried the fleet a great distance, the legions disembarked on Parthian beaches at a spot within a few days’ march of the road leading to Ctesiphon, where the royal palace of the Parthians was located. There the king was spending his time peacefully, thinking that the battles between Severus and the Hatrenians were no concern of his.

But the troops of the emperor, brought by the current to these shores against their will, landed and plundered the region, driving off for food all the cattle they found and burning all the villages as they passed. After proceeding a short distance, they stood at the gates of Ctesiphon, the capital city of the great king Artabanus. [28 January 198] The Romans fell upon the unsuspecting barbarians, killing all who opposed them. Taking captive the women and children, they looted the entire city. After the king fled with a few horsemen, the Romans plundered the treasuries, seized the ornaments and jewels, and marched off. Thus, more by luck than good judgment, Severus won the glory of a Parthian victory. And since these affairs turned out more successfully than he had any reason to hope, he sent dispatches to the senate and the people, extolling his exploits, and he had paintings of his battles and victories put on public display. The Senate voted him the titles formed from the names of the conquered nations, as well as all the rest of the usual honors.– Herodian, Roman History, III 9

However, like Trajan almost a hundred years earlier, Severus was unable to capture the Hatra fortress, despite the two long sieges. It is also worth mentioning that Severus ordered to extend Limes Arabicus, building new fortifications in the Arabian desert, from Basia to Dumata.

Severus’s relationship with the Roman Senate was never good. The emperor relied on the eminences, limited the Senate’s influence to a minimum, and appointed all officials, including consuls. The senators did not like him because of his reliance on the legions when he came to power. Septimius got his revenge with numerous accusations of corruption and conspiracy. The ruler issued many death sentences on senators, who were replaced with his supporters.

After arriving in Rome in 193 CE, Severus, as it was mentioned earlier, decided to dissolve the Praetorian Guard. Pretorians who took part in these activities were forced to take off their ceremonial armour and were forbidden to approach the city for c. 140 km under the penalty of death. In place of the old guard, Severus set up a new unit of 50 000 loyal soldiers who camped in Albanum, near Rome (presumably to guarantee more power for the emperor).

During his reign, Severus increased the number of legions from 25/30 existing to 33 (three new legions called Parthian). In addition, he increased the number of auxilia (numerii), which were mostly complemented with warriors from the eastern areas of the Empire. In addition, the legionary’s salary increased from 300 to 500 denarii. To gain the support of the army, he allowed legionaries to marry, own land, and live in cities outside the camps – before completing their service. However, this reform was not aimed at reducing the discipline in the Roman army but was only legalizing the real state of affairs.

Severus admired law from early childhood. As an emperor, he surrounded himself with lawyers. He tried to defend the poor (humiliores) against the rich (honestiones) and take care of all the inhabitants of the Empire. He expanded the central administration with two new imperial offices. Many of the African cities were granted the status of municipia, as well as the law of Italy, thus exempting them from taxes. For strategic reasons and to prevent civil wars, he divided larger provinces of the empire, such as Syria, into smaller units.

Severus’ reign was also characterized by the persecution of the Christians. Local authorities did not seek out Christians, but if a Christ-follower had already been discovered, they were told to renounce Jesus and offer the Roman deities a sacrifice. If he had not done that, he would have been sentenced to death. In 202 CE, Severus issued a decree that banned the admission of Christian and Jewish faith and assemblies, which intensified the repression of these groups (the martyrdom of Saint Irenaeus or Saint Perpetua). The edict was also of some importance in the context of baptizing infants in Christianity.

In late 202 CE, Severus started a campaign in Africa. In his name, the legate of legio III Augusta, Quintus Anicius Faustus fought the Garamantes along the Limes Tripolitanus for five years, occupying a number of settlements, including Cydamus, Gholaia, Garbia and the capital Garama, which was located about 600 km south of Leptis Magna.

During this time, fights were also fought in Numidia, which was extended to the settlements of Vescera, Castellum Dimmidi, Gemellae, Thabudeos, Thubunae and Zabi. Until 203, n.e. the entire southern border of Roman Africa has been clearly expanded and fortified. The desert Nomads could no longer safely invade Roman lands from the desert. Severus managed to secure southern limes.

In 208 CE Septimius Severus went to Britain with an ambitious plan to conquer Caledonia(today’s Scotland). The ruler appeared there with 40 000 soldiers. This is how Herodian describes these events:

[…]In the midst of the emperor’s distress at the kind of life his sons were leading and their disgraceful obsession with shows, the governor of Britain informed Severus by dispatches that the barbarians there were in revolt and overrunning the country, looting and destroying virtually everything on the island. He told Severus that he needed either a stronger army for the defense of the province or the presence of the emperor himself. Severus was delighted with this news: glory-loving by nature, he wished to win victories over the Britons to add to the victories and titles of honor he had won in the East and the West. But he wished even more to take his sons away from Rome so that they might settle down in the soldier’s life under military discipline, far from the luxuries and pleasures in Rome. And so, although he was now well advanced in years and crippled with arthritis, Severus announced his expedition to Britain, and in his heart he was more enthusiastic than any youth.

During the greater part of the journey he was carried in a litter, but he never remained very long in one place and never stopped to rest. He arrived with his sons at the coast sooner than anyone anticipated, outstripping the news of his approach. He crossed the Channel and landed in Britain; levying soldiers from all these areas, he raised a powerful army and made preparations for the campaign. Disconcerted by the emperor’s sudden arrival, and realizing that this huge army had been assembled to make war upon them, the Britons sent envoys to Severus to discuss terms of peace, anxious to make amends for their previous errors. Seeking to prolong the war so as to avoid a quick return to Rome, and still wishing to gain a victory over the Britons and the title of honor too, Severus dismissed the envoys, refusing their offers, and continued his preparations for the war. He especially saw to it that dikes were provided in the marshy regions so that the soldiers might advance safely by running on these earth causeways and fight on a firm, solid footing.– Herodian, Roman History, III 14

He strengthened Hadrian’s Wall and Antoninus Wall and also reconquered the Southern Uplands. South of this wall was built a 165-acre camp in Trimontium (today’s Newstead), in which the army was stationed. Then the Roman forces set off north into the enemy territory. The emperor led the army in the footsteps of Julius Agricola, rebuilding abandoned camps and erecting new fortifications along the east coast, including Carpow, which could accommodate 40 000 soldiers.

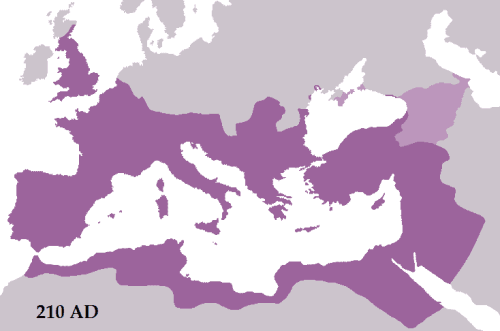

Up to 210 CE Severus’ campaign was very successful despite the Caledonian’s drive tactics and the big losses in the Roman army. The Caledonians were seeking peace, which the emperor guaranteed only on the condition they relinquish control of the Central Lowlands. This may be perceived as evidence for the theory that Severus wanted to create another line of fortifications there.

Caledonians, while losing supplies and feeling that the situation is tragic, led to the formation of confederation, the so-called Maeatae and the uprising against the Romans. Severus had been already preparing another war campaign that aimed at exterminating and enslaving the Caledonian population. Plans, however, were thwarted by the emperor’s unexpected illness.

Death

He died on 4 February 211 CE during a trip to Britain in Eboracum (today’s York). On his deathbed he was to advise his sons: “Live in harmony, enrich soldiers, and besides, you can despise all.” This is how it is presented by the historian Herodian:

Now a more serious illness attacked the aged emperor and forced him to remain in his quarters; he undertook, however, to send his son out to direct the campaign. Caracalla, however, paid little attention to the war, but rather attempted to gain control of the army. Trying to persuade the soldiers to look to him alone for orders, he courted sole rule in every possible way, including slanderous attacks upon his brother. Considering his father, who had been ill for a long time and slow to die, a burdensome nuisance, he tried to persuade the physicians to harm the old man in their treatments so that he would be rid of him more quickly.note After a short time, however, Severus died, succumbing chiefly to grief, after having achieved greater glory in military affairs than any of the emperors who had preceded him. No emperor before Severus won such outstanding victories either in civil wars against political rivals or in foreign wars against barbarians. Thus Severus died after ruling for eighteen years, and was succeeded by his young sons, to whom he left an invincible army and more money than any emperor had ever left to his successors.

– Herodian, Roman History, III 15

After his death, Severus was deified by the Senate as divus Septimius Severus. His sons Caracalla and Geta took over the power, supported by their mother, Julia Domna.

Caracalla continued his father’s warfare, but with time he decided to establish a truce. Never again in later times, the Romans did not venture so deeply into Caledonia. In time, they withdrew to the south, establishing the Hadrian’s Wall as the northern border of the Empire.

Summary

Severus’ reign was certainly successful in the state’s interest. Septimius was a strong and ambitious ruler that the state needed at that time. Rome became more centralized and strengthened. Limes Tripolitanus was enlarged, which protected Africa from the south and guaranteed a constant supply of grain to the capital. Victory over the Parthians was definitive and allowed to establish a new status quo in the east. His policy of expansion and increase in pay strained the budget, which was also criticized by the historians such as Cassius Dio and Herodian. Society could feel the greater burden of tax, which was intended mainly to keep the legions at the borders. In addition, the Roman coin was depreciated.

Severus was also famous for many buildings he erected. In addition to the triumphal arch in the Roman Forum, his name is associated with the so-called Septizodium, the object built-in 203 CE, which probably did not have more practical functions, only a decorative one. In addition, the emperor clearly enriched his native city of Leptis Magna, in which he created another triumphal arch on the occasion of his visit in 203 CE. Flavian Palace, the residence of Roman emperors on Palatine Hill was also renovated.