Chapters

Ancient Rome from the beginning of its existence consisted of two social layers – patricians and plebeians; higher and lower state respectively. Lack of influence on state decisions and the use of plebe by patricians led to the so-called secessio plebis that took place five times in Rome’s history.

The early Roman republic was headed by two consuls (executive power) and a senate (legislative power). Both institutions were available only to patricians. The most important and most powerful Roman families concentrated in their hands the full power they exchanged with each other. In their opinion, members of the pleb had only economic and military value, which was regularly used. Moreover, the public land acquired as a result of hostilities was accumulating in the hands of gens (the most important Roman families), who were further away in property from the plebe.

First secession of the plebeians – 494 BCE

In 495 BCE plebeians began to express their dissatisfaction with the debt they had towards the patrician layer. An enormous number of Roman farmers were mobilized for the war with the Latins, winning the battle at Lake Regillus. Plebeians, being at war, were not able to generate profits from their farms. As a result, he had to get into debt to support himself and pay taxes. Lack of debt repayment allowed the lenders to torture and exploit former soldiers; and even enslave them.

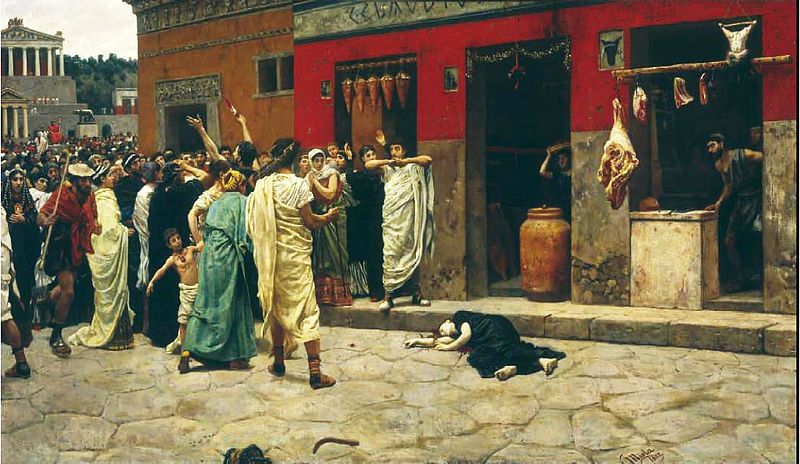

Roman historian, Titus Livy describes the story of how an elderly man with scars on his skin (this proved his dedication on the battlefield), pale and sick with leather, a long beard, clad in worn clothes, he fell to the ground in the Forum Romanum – the city centre. There he told other citizens his story. As it turned out, he was an officer of the Roman army in the war against the Sabines. During the conflict, his farm was burned and cattle were killed by an enemy army. Moreover, a tax was imposed on him that he was unable to pay. He had to take a loan, which he had nothing to cover. As a result, he lost his grandfather’s and father’s farm. Lack of further funds to pay the debt meant that he was imprisoned, threatened with death and scourged.

An angry crowd gathered at the Roman Forum and demanded reactions and reforms on the part of consuls: Servilius and Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis and the Senate. Finally, plebeians listened to Servilius, who needed recruits to fight the Volsci who invaded Rome’s Latin allies. To calm the crowd, the consul announced that no citizen would be imprisoned for refusing to appear in military service. Moreover, if a legionary participates in hostilities, his debt assets will not be confiscated or sold; and his children and grandchildren will not be arrested. Debtors in prisons were released immediately. The consul’s actions calmed the crowd and allowed him to gather an army with which he defeated Volsci.

After returning from hostilities, plebeians demanded specific decisions to improve the fate of the oppressed. Lack of danger from the outside caused the patricians to feel strong again and, through the second consul – Appius – took steps to enforce debts and imprison those who were unable to settle their obligations. The outraged crowd demanded a reaction from Servilius, who promised them reforms before the war. Servilius – despite his sincere intentions – was not able to win the support of the aristocracy. He was thus hated by both camps: the plebeians considered him a traitor; patricians for a weakling.

Another threat was the combined invasion of Volsci, Sabines and Aequi to the Roman lands in 494 BCE. At this hard time, Manius Valerius Maximus was appointed dictator, who led the legions to victory. After returning to the capital, the dictator decided to ask the Senate to regulate the issue of debts that troubled his soldiers. However, the lack of unambiguous decisions and the slowness of senators meant that Valerius renounced his position. His involvement, however, was appreciated by plebeians.

Another threat from Aequi forced the senate to announce the recruitment again. The plebe, already completely discouraged from patriciate and their unproven promises, did not appear for conscription. What’s more, at the call of one Lucius Sicinius Vellutus, it was decided to leave Rome en masse. Most of the citizens of the “Eternal City” went to the nearby Mons Sacer, behind the Anio River. A fort was built there, with ditches and embankments around it. lex sacrata was voted, which resulted in exsecratio – Jupiter’s anger in case of breaking the bill. The office of tribuni plebis was established, which was given the range of powers and the rank of an official.

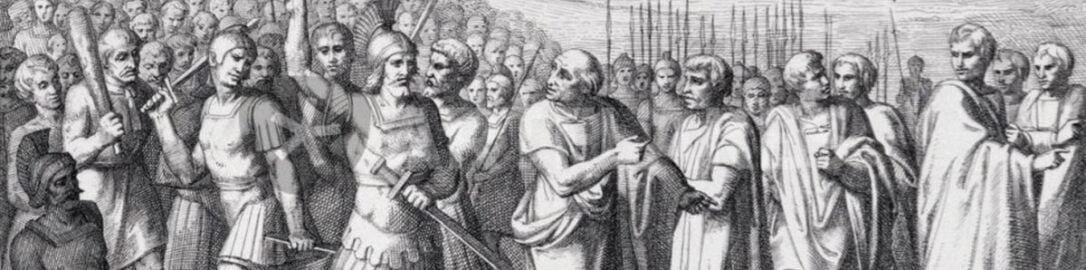

Senate, realizing that Rome would not defend itself solely with the help of patricians, decided to send an emissary who would make a settlement with the separatists. Agrippa Consul Menenius Lanatus convinced the plebeians to return by comparing Rome to the human body. He suggestively demonstrated that both plebeians and patricians must work together to keep the Republic alive1. The plebeians were impressed by this comparison, which suggested that they were as important as the ruling layer.

Finally, a settlement was reached, which assumed the official establishment of the said office – the tribune of plebs (originally there were five officials), which was to protect the rights of the plebeians and was elected only by plebeians. The tribune protected plebeians from the consul authorities; moreover, he was guaranteed security – violation of the tribune’s inviolability was punishable by death (sacrosancti).

The above law initiated further concessions in favour of plebeians. In 493 BCE the presidency and the consulate were held for the first time by plebeians (but this was not legally established). In 456 BCE, lex Icilia was established, which allowed the presbytery to use the land in Aventine.

Second plebeian secession – 449 BCE

In 451 BCE it was decided to establish a decemvir office (decemviri) – “council of ten”2 – which was to codify Roman law. The special college had full power, and all its decisions were not subject to appeal. The decemvirate was created largely on the initiative of plebeians who wanted to be able to evade the customary laws applied by senior patricians. What is important, however, the office was established only by the patriciate. To this end, the term of office has been limited to one year to avoid tyrannical tendencies.

The first college – constituted solely by patricians – published 10 tables of laws, which were however considered incomplete. After the end of the term of office, the college’s activities were not abandoned. The new decemvirate also joined the plebeians, which, however, did not change the nature of the new power. The Decemvirs severely limited some of the institutions, including the tribune of plebs. There was a form of tyranny, aimed mainly against plebeians. There was also outrageous behaviour by officials. One of the tribune of plebs was killed for criticizing the decemvir. What’s more, a certain Appius Claudius Crassus – a plebeian representative coming from the patriciate and who was the only one present for both terms – wanted to force a woman named Virginia to marry him (he used a trick here, forcing the girl’s father – Verginius – to enslave his daughter and selling it to decemvir). To prevent this, the centurion’s father killed his own daughter to preserve her honour and cursed the decemvir. These events were one of the factors that caused riots among the pleb, which then went to Aventine. Then went to Mons Sacer, as during the first secession. The Senate, shocked by another revolt, demanded the resignation of 10 extraordinary officials who, after their first refusals, finally gave up.

Still, the plebeians were reluctant to patricians, who once again did not respect former rights. The plebeians demanded that the position of the tribune of plebs be restored, which guaranteed their security and rights. Thanks to Lucius Valerius Potitus and Marcus Horatius Barbatus in 449 BCE, a new law was adopted – the so-called lex Valeria Horatia de plebiscitis – which granted more rights to plebeians. From then on, the resolutions concilium plebis (plebiscita – “plebiscites”) were to apply to all citizens, i.e. they were on behalf of the state. However, they still required approval by the Senate (auctoritas patrum).

The law of the XII Tablets was the victory of plebeians, who from then on demanded the ruling patriciate to comply with written laws, not customary norms. On the other hand, it should be noted that the written laws did not regulate practically any problems faced by plebeians. The debt of the debtors was still not alleviated, farmers did not have access to ager publicus; moreover, the patriciate separated from the plebeians by the prohibition of entering into mixed marriages. It should be noted, however, that codification was a form of compromise between those holding gens and those demanding respect for the lower state.

Third plebeian secession – 445 BCE

In 445 BCE, there were voices complaining about the prohibition of marriages between patricians and plebeians, which was introduced in 450 BCE, under the rights of XII tables. It was naturally a patrician initiative that wanted to protect the blood of its families and maintain offices for gens.

In 445 BCE one of the tribunes of plebs was Gaius Canuleius, who proposed to withdraw the act (rogatio) of 450 and to appoint one of the consuls from the pleb. The tribune emphasized the fact that in the history of Rome, there were many noble Roman citizens coming from plebeians who worked for the state. Initially, the Canuleius legislative initiative met with clear opposition from patricians. However, after another military secession, the lex Canuleia was successfully enforced. Under it, mixed marriages were allowed and a military tribunal with consular authority (tribuni militum consulari potestate) was established, which was available to plebeians and had consular-like authority. Their number has changed (from 3 to 16) over the years. With the leges Liciane Sextiae, the office disappeared in 367 BCE, as the plebeians’ right to occupy one of the consulate’s seats was officially recognized (however, this was not fully guaranteed).

Fourth plebeian secession – 342 BCE

Mentioned by Titus Livy. As a result of the fourth rebellion, a law was officially adopted (thanks to the tribune of Lucius Genucius), which officially confirmed that plebeians had the right to one of the consuls.

Fifth secession of plebeians – 287 BCE

In 287 BCE there was a fifth and last revolt. Its reason was the distribution of the land acquired on Sabines only among patricians. Moreover, returning from the war, plebeians had problems paying off the debts they had incurred. A situation that has repeated itself has caused agitation. Masses of plebeians went to Janiculum as a protest.

In order to solve the problem and end the rebellion, a plebeian – Quintus Hortensius – was appointed as a dictator, who persuaded the crowd to return home. Then Hortensius announced the law – the so-called lex Hortensia – which recognized decisions taken in plebiscites as binding the entire Roman society (without the approval of the Senate).

This event officially ended public unrest and strengthened the position of plebeians in relation to patricians. All subsequent laws achieved by the plebeians had a decisive influence on the formation of a new social group – nobles, i.e. wealthy landowners from both patricians and plebeians. Gradually politics, the highest offices and honours in the state were available to everyone.