Chapters

The life of a Roman legionary (legionarius) was beyond all doubt very difficult and demanded enormous stamina. Volunteers (or recruits) were very often not sure whether they would come back home after sixteen years of service (in 5 CE the length of service was prolonged to 20 years). Both the legionaries’ duties and the discipline were supposed to create true men out of them, ready to win the battle against the stronger enemy.

More about a recruit in the Roman army

The legionaries were recruited between the age of 17 to 20 for sixteen years of service (The Marian Reforms). According to Vegetius, the Roman legionary should measure about 170 cm. Higher citizens could also join the army, and the standard for horsemen or the first legionary cohorts was about 180 cm.

Carried out Geoffrey Kron’s research, conducted on 926 adult male skeletons buried in Italy between the years 500 BCE and 500 CE confirmed that on average population was around 168 cm tall. Perhaps there was a height selection introduced to the Roman army for the legionaries had to keep the alignment in the right order (e.g. testudo).

Were Roman legionaries really short?

After hard training and everyday military drill, Roman legionaries were able to march 37,5 kilometres a day with bagage weighing even 36 kilograms. Gaius Marius’ one exercise was a long-distance run with full equipment.

From the very beginning, the young recruits’ previously acquired abilities were being properly used. If someone used to be a smith, he became an armourer, a shoemaker who sewed shoes for the soldiers, and those who specialized in wood processing built war engines. If somebody had no such ability, he could easily become a member of the surveyor’s group or the one responsible for cleaning the roads. Those were the legionaries’ duties when there were no battles, but once the trumpets gave a signal to fight, all of them were to be ready at their post and fully armed.

There was a division into experienced, veterans and young ones. The older and more experienced legionaries were telling stories and teaching the younger generation how to behave on the battlefield.

Also, the functions differed. The veterans were seeded in the middle of the fight or somewhere they could clinch the result of the battle and the younger soldiers’ main aim was simply to immobilize the enemy.

The matter of food is also worth mentioning as it was far different from what we can imagine nowadays. The bread was the major component of the legionaries’ diet – the daily wheat ration was approximately 8.7 litres. They ate hardly any meat or vegetables which were considered not valuable. The small portion of proteins consumed by the Romans was the reason for their poor bones growth and, as a result, for their short stature. On the other hand, as was already mentioned, the main component of the Gallic and Germanic diet was meat. Of course, it does not mean the Romans were only vegetarians. On their menu, there were also such things as beef, pork, lamb, and game. In Britain, venison or goat meat was available whereas in Egypt it was possible to get veal and different fish species.

Roman legionaries were drinking diluted wine (daily ration approximately 0,27 litres) or beer. It happened sometimes that the larger amount of alcohol led to some struggles. According to Tacitus, a historian of the Roman Empire, once when legionaries and Gauls from the auxiliary formation were feasting together in Ticinium in 69 CE, a friendly wrestling competition turned into a fight as one of the Gauls started to laugh at a defeated Roman soldier. The struggle quickly boiled into a riot and about 1000 people were killed as a result.

Legionaries could not allow themselves to make any mistakes since they were strictly punished for each. A sentry caught sleeping during his watch was either killed or penalized. Supposedly Roman soldiers developed a particular way of sleeping during the watch – bracing the whole body on the shield. Also in case the soldier responsible for building the camp was caught without his gladius, then he was condemned to death.

Discipline

The Roman army was highly disciplined which was mainly the result of tribunes’ and centurions’ inspections. The general review of a drill, soldiers’ tasks or checking the state of the weapons were considered encouraging. It was both a way to organize well their free time and form a habit of reliability and responsibility for the military property.

The reality of the Roman army was well known by Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, a Roman historian and writer from the second half of the 4th century. He was a treasury administrator who was keen on military and horse breeding. His opus magnum is (Epitoma rei militaris) dedicated to the reigning emperor (probably Theodosius). It consists of 4 books and is the only surviving ancient manual of the Roman military. Vegetius’ main idea was his deep belief that once the strict discipline from the past would be restored in the Roman army, so would be the power of Rome. In the epitome, he describes, for example, the adaptation of the Hunnic Composite Bow but he mainly focuses on the battle techniques and war tactic.

This is one of the passages describing the position of the centurion:

The centurion in the infantry is chosen for his size, strength and dexterity in throwing his missile weapons and for his skill in the use of his sword and shield; in short for his expertness in all the exercises. He is to be vigilant, temperate, acctive and readier to execute the orders he receives than to talk; Strict in exercising and keeping up proper discipline among his soldiers, in obliging them to appear clean and well-dressed and to have their arms constantly rubbed and bright (…) The splendor of the arms has no inconsiderable effect in striking terror into an enemy.. Can that man be reckoned a good soldier who through negligence suffers his arms to be spoiled by dirt and rust?

– Vegetius, Epitoma rei militaris

Here he describes the role of a military tribune:

Nothing does so much honor to the abilities or application of the tribune as the appearance and discipline of the soldiers, when their apparel is neat and clean, their arms bright and in good order and when they perform their exercises and evolutions with dexterity.

Of course, the legionaries were prized for an extraordinary engagement in the exercises and fulfilling their duties.

Those who, expert in their exercises, receive a double allowance of provisions, are called Armature Duplares, and those who have but a single portion, Simplares. The Mensores mark out the ground by measure for the tents in an encampment, and assign the troops their respective quarters in garrison. The Torquati, so denominated from the gold collars given them in reward for their bravery, had besides this honor different allowances. Those who received double were called Torquato Duplares, and those who had only single, Simplares. There were, for the same reason, Candidatii Duplares, and Candidate Simplares. These are the principal soldiers or officers distinguished by their rank and privileges thereto annexed. The rest are called Munifices, or working soldiers, from their being obliged to every kind of military work without exception

– Vegetius, Epitoma rei militaris

Vegetius also discusses commanding the army:

[…] A commander-in-chief therefore, whose power and dignity are so great and to whose fidelity and bravery the fortunes of his countrymen, the defense of their cities, the lives of the soldiers, and the glory of the state, are entrusted, should not only consult the good of the army in general, but extend his care to every private soldier in it. For when any misfortunes happen to those under his command, they are considered as public losses and imputed entirely to his misconduct. If therefore he finds his army composed of raw troops or if they have long been unaccustomed to fighting, he must carefully study the strength, the spirit, the manners of each particular legion, and of each body of auxiliaries, cavalry and infantry. He must know, if possible, the name and capacity of every count, tribune, subaltern and soldier. He must assume the most respectable authority and maintain it by severity. He must punish all military crimes with the greatest rigor of the laws. He must have the character of being inexorable towards offenders and endeavor to give public examples thereof in different places and on different occasions.

– Vegetius, Epitoma rei militaris

Free time

Roman soldiers willingly enjoyed the variety of services provided by the merchants, craftsmen, and prostitutes. When the army settled somewhere, there was a provisional camp built around the fort which soon transformed into a village or a small town. Sometimes drunk soldiers caused trouble while wandering around. A merchant’s complaint to the officer in Vindoland (from c. 120 CE) survived and it says:

[…] he beat me all the more… goods… or pour them down the drain. As befits an honest man I implore your majesty not to allow me, an innocent man, to have been beaten with rods and, my lord […] as if I had committed some crime.

– Tablet 344 from Vindolanda

During festivals and holidays, Roman legionaries used to meet at a feast organized by the military clubs collegia militares, which were responsible for taking care of the soldiers. Sometimes next to the walls there were built quite large amphitheatres for the gladiator fights. For instance, the auditorium in Careleon in Wales could sit even 6000 people whereas the one in Carnutum in Austria could sit an even bigger audience. In Roman camps, there were also baths which performed not only hygienic but also integrative functions. It was possible either to clean the body and exercise or enjoy wine with friends in the entertainment room.

Legionaries exercises

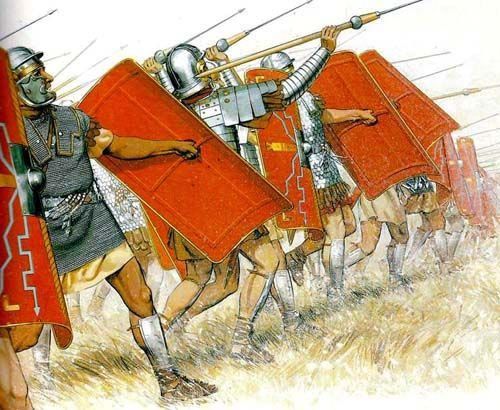

Most of all, the recruits had to learn a long-distance march – every month the soldiers had to travel the distance of 30 kilometers, fully equipped. Half of the distance they marched and the other half ran. They were also taught how the build a camp, they practised stone-throwing, swimming, and horse riding. Twice a day they exercised (veterans only once), they had to learn how to jump on and off the horse (from both sides which was no mean feat taking into considerations that there were no stirrups then) with full equipment. Nonetheless the most important of all was the ability to use the weapon.

The stake was fixed in the ground, about the height of a human being. The soldier armed with a wicker shield and wooden, blunt sword (lat. rudis; even heavier than a normal one) attacked the stake and exercised. Moreover, he had to throw a pilum and participate in pretended battles whereby the weapons were protected with cases in order to avoid any potential injuries.

Family

In the reign of Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) the legionaries were forbidden to marry with the aim of keeping the discipline and not attaching the soldiers to the place they were stationed. Theoretically, the law stood for the next two centuries however, given that the service lasted 25 years, it was impossible to expect from the legionaries that they would not marry and start a family. In view of the fact that their place of living was associated with the military unit they served in, most of the soldiers married local women. Their relationships were recognized by the army but not by the country. It is worth mentioning that a legionary was perceived by the women as a good catch as he had a steady income and guaranteed stabilization. Children from such marriages very often maintained family tradition and joined the army which was not meaningless in the time of the recruitment crisis. Boys joined their fathers’ units and had a career in the army. The officers winked at the soldiers sneaking out to their families living outside the fort. Furthermore, it happened sometimes that a cohabitant moved into the camp with children to share contubernium with her husband – there is evidence for that, some articles of daily use found in the barracks.

The legionaries kept in touch with their families, they corresponded sending not only letters but also packages. Claudius Terentius, for example, wrote to his father:

And if god should be willing, I hope to live frugally and to be transferred to a cohort; but here nothing will be accomplished without money, and letters of recommendation have no value unless a man helps himself.

– Letter P.Mich.inv. 5390

How was a Roman legionary perceived?

In the judgments of those more favorable people, such as Plutarch, Augustus’ reform was perceived as the fruition of Plato’s conception presented in Republic – permanent, well-trained army. The legions were seen as a group of soldiers-citizens favored with service because of their natural abilities, developed by training. Those people let the rest of the citizens devote themselves to their professions. Thus they were not soldiers out of necessity. Plato wanted the army to receive a payment sufficient to fulfill their needs, as compensation. Interestingly, Plato’s supporters believed that soldiers had to fulfill particularly strict moral requirements. This belief was clearly present in the nomenclature used eg. by Dio Chrysostom who officially called the soldiers of the Late Roman Empire the noblest (gr. gennaiataioi).

Cassius Dio’s conception seems to be much more realistic. It simply says that if utility overweighs integrity, then the stronger and poorer (mainly criminals) should be used for the common good. It may be treated as an unusual way of adjustment to the times when money mattered more than glory.

Even in Horace’s poems a soldier appears as the one who needs to disown his otium (free time), get rid of personal liberty and subject himself to the authority in order to earn money for not so prosperous senectitude.

As a result of forming a professional army, many citizens could devote themselves entirely to their professions and therefore probably enjoyed being released from their military duty. Of course, it did not interfere with them in grieving in public for “the old Roman morality and mentality”. According to the other conception, a soldier had a position of a degenerate citizen-decadent and could be consequently considered as such despite the fact that most of the soldiers were citizens or foreigners trying to become ones.

At Tacitus, we can observe a particular reversal of platonic standards. The noble anger characteristic for the first soldiers turned into ira or furor which means fury and ferocity. It made a good-natured platonic soldier (whom nota bene Plato called A Purebred Dog) a beast lusting only gold and sometimes glory. In the name of those, such a beast was able to lay a hand on this common good that he had promised to protect.

Such ideology, especially in the 4th century CE had a strong impact on the upper class. It created the image of a soldier who should be from a lower class, separated from the rest of society and being paid frugally in order not to make him too proud and, finally, he should be completely obedient and subject to a strict discipline. Those harsh requirements were being motivated by the statement: “if the platonic dog became a wolf now it is the commanders’ responsibility to make him come to his senses”.

The Roman legionary, depending on circumstances filled with either respect and admiration or fear and contempt.